Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt

Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt | |

|---|---|

| 754 BC–656 BC | |

![Statues of various rulers of the late 25th Dynasty–early Napatan period. From left to right: Tantamani, Taharqa (rear), Senkamanisken, again Tantamani (rear), Aspelta, Anlamani, again Senkamanisken; Kerma Museum.[1] of Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Rulers_of_Kush%2C_Kerma_Museum.jpg/300px-Rulers_of_Kush%2C_Kerma_Museum.jpg) Statues of various rulers of the late 25th Dynasty–early Napatan period. From left to right: Tantamani, Taharqa (rear), Senkamanisken, again Tantamani (rear), Aspelta, Anlamani, again Senkamanisken; Kerma Museum.[1] | |

![Kushite heartland, and Kushite Empire of the 25th dynasty of Egypt, circa 700 BC.[2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/07/Kushite_heartland_and_Kushite_Empire_of_the_25th_dynasty_circa_700_BCE.jpg/250px-Kushite_heartland_and_Kushite_Empire_of_the_25th_dynasty_circa_700_BCE.jpg) Kushite heartland, and Kushite Empire of the 25th dynasty of Egypt, circa 700 BC.[2] | |

| Capital | Napata Memphis |

| Common languages | Egyptian, Meroitic |

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Pharaoh | |

• 744–712 BC | Piye (first) |

• 664–656 BC | Tantamani (last) |

| History | |

• Established | 754 BC |

• Disestablished | 656 BC |

The Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XXV, alternatively 25th Dynasty or Dynasty 25), also known as the Nubian Dynasty, the Kushite Empire, the Black Pharaohs,[2][3] or the Napatans, after their capital Napata,[4] was the last dynasty of the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt that occurred after the Nubian invasion.

The 25th dynasty was a line of pharaohs who originated in the Kingdom of Kush, located in present-day northern Sudan and Upper Egypt. Most of this dynasty's kings saw Napata as their spiritual homeland. They reigned in part or all of Ancient Egypt for nearly a century, from 744 to 656 BC.[5][6][7][8]

The 25th dynasty was highly Egyptianized, using the Egyptian language and writing system as their medium of record and exhibiting an unusual devotion to Egypt's religious, artistic, and literary traditions. Earlier scholars have ascribed the origins of the dynasty to immigrants from Egypt, particularly the Egyptian Amun priests.[9][10][11] The third intermediate-period Egyptian stimulus view is still maintained by prominent scholars, especially that excavations from el-Kurru cemetery, the key site to the origin of the Napata state, show sudden Egyptian arrivals and influence during the 3rd intermediate period, concurrent with the Egyptianization process.[12][13]

The 25th Dynasty's reunification of Lower Egypt, Upper Egypt, and Kush created the largest Egyptian empire since the New Kingdom. They assimilated into society by reaffirming Ancient Egyptian religious traditions, temples, and artistic forms, while introducing some unique aspects of Kushite culture.[14] It was during the 25th dynasty that the Nile valley saw the first widespread construction of pyramids (many in what is now Northern Sudan) since the Middle Kingdom.[15][16][17]

After Sargon II and Sennacherib defeated attempts by the Nubian kings to gain a foothold in the Near East, their successors Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal invaded, defeated, and drove out the Nubians, in the Assyrian conquest of Egypt. The fall of the 25th Dynasty marks the start of the Late Period of ancient Egypt. The Twenty-sixth Dynasty was initially a puppet dynasty installed by and vassals of the Assyrians, and was the last native dynasty to rule Egypt before the invasion by the Persian Achaemenid Empire.

The traditional representation of the dynasty as "Black Pharaohs" has attracted criticism from scholars, specifically because the term suggests that other dynasties did not share similar southern origins.[18] They also argue that the term overlooks the genetic continuum that linked ancient Nubians and Egyptians.[19][20]

History

Piye

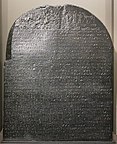

The twenty-fifth dynasty originated in Kush, which is presently in Northern Sudan. The city-state of Napata was the spiritual capital and it was from there that Piye (spelled Piankhi or Piankhy in older works) invaded and took control of Egypt.[21] Piye personally led the attack on Egypt and recorded his victory in a lengthy hieroglyphic filled stele called the "Stele of Victory." The stele announces Piye as Pharaoh of all Egypt and highlights his divine kingship by naming him "Son of Re" (Ruler of Lower Egypt) and "Beloved of Amun" (Ruler of Upper Egypt).[7]: 166 Piye's success in achieving the double kingship after generations of Kushite planning resulted from "Kushite ambition, political skill, and the Theban decision to reunify Egypt in this particular way", and not Egypt's utter exhaustion, "as frequently suggested in Egyptological studies."[16] Piye revived one of the greatest features of the Old and Middle Kingdoms, pyramid construction. An energetic builder, he constructed the oldest known pyramid at the royal burial site of El-Kurru. He also expanded the Temple of Amun at Jebel Barkal[16] by adding "an immense colonnaded forecourt."[7]: 163–164

Piye made various unsuccessful attempts to extend Egyptian influence in the Near East, then controlled from Mesopotamia by the Semitic Neo-Assyrian Empire. In 720 BC he sent an army in support of a rebellion against Assyria in Philistia and Gaza, however, Piye was defeated by Sargon II, and the rebellion failed.[24] Although Manetho does not mention the first king, Piye, mainstream Egyptologists consider him the first Pharaoh of the 25th dynasty.[15][16][17][25] Manetho also does not mention the last king, Tantamani, although inscriptions exist to attest to the existence of both Piye and Tantamani.

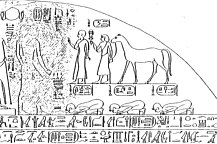

The Stele of Piye inscription describes Piye as very religious, compassionate, and a lover of horses.[26] Piye scolded those that abused horses, demanded horses as gifts, and had eight of his horses buried with him.[26] Studies of horse skeletons at el Kurru, textual evidence, and iconographical evidence related to the use of horses in Kushite warfare indicate that "the finest horses used in Egypt and Assyria were bred in, and exported from Nubia."[7]: 157–158 Better horses, chariots, and the development of cavalry tactics helped Piye to defeat Tefnakht and his allies.[7]: 158

Shabaka and Shebitku Chronology Dispute

Although the Manethonic and classical traditions maintain that it was Shabaka's invasion which brought Egypt under Kushite rule, the most recent archaeological evidence shows that Shabaka ruled Egypt after Shebitku and not before, as previously thought. The confusion may stem from Shabaka's accession via Kushite collateral succession versus Egyptian patrilinear succession.[7]: 168 The construction of the tomb of Shebitku (Ku. 18) resembles that of Piye (Ku. 17) while that of Shabaka (Ku. 15) is similar to that of Taharqa (Nu. 1) and Tantamani (Ku. 16) [39 – D. Dunham, El-Kurru, The Royal Cemeteries of Kush, I, (1950) 55, 60, 64, 67; also D. Dunham, Nuri, The Royal Cemeteries of Kush, II, (1955) 6–7; J. Lull, Las tumbas reales egipcias del Tercer Periodo Intermedio (dinastías XXI-XXV). Tradición y cambios, BAR-IS 1045 (2002) 208.] .[27] Secondly, Payraudeau notes in French that "the Divine Adoratrix Shepenupet I, the last Libyan Adoratrix, was still alive during the reign of Shebitku because she is represented performing rites and is described as "living" in those parts of the Osiris-Héqadjet chapel built during his reign (wall and exterior of the gate) [45 – G. Legrain, "Le temple et les chapelles d’Osiris à Karnak. Le temple d’Osiris-Hiq-Djeto, partie éthiopienne", RecTrav 22 (1900) 128; JWIS III, 45.].[27] In the rest of the room it is Amenirdis I, (Shabaka's sister), who is represented with the Adoratrix title and provided with a coronation name. The succession Shepenupet I – Amenirdis I thus took place during the reign of Shebitku/Shabataqo. This detail in itself is sufficient to show that the reign of Shabaka cannot precede that of Shebitku/Shabataqo.[27] Finally, Gerard Broekman's GM 251 (2017) paper shows that Shebitku reigned before Shabaka since the upper edge of Shabaka's NLR #30's Year 2 Karnak quay inscription was carved over the left-hand side of the lower edge of Shebitku's NLR#33 Year 3 inscription.[28] This can only mean that Shabaka ruled after Shebitku.

Shebitku

According to the newer chronology, Shebitku conquered the entire Nile Valley, including Upper and Lower Egypt, around 712 BC. Shebitku had Bocchoris of the preceding Sais dynasty burned to death for resisting him. After conquering Lower Egypt, Shebitku transferred the capital to Memphis.[28] Dan'el Kahn suggested that Shebitku was king of Egypt by 707/706 BC.[29] This is based on evidence from an inscription of the Assyrian king Sargon II, which was found in Persia (then a colony of Assyria) and dated to 706 BC. This inscription calls Shebitku the king of Meluhha, and states that he sent back to Assyria a rebel named Iamani in handcuffs. Kahn's arguments have been widely accepted by many Egyptologists including Rolf Krauss, and Aidan Dodson[30] and other scholars at the SCIEM 2000 (Synchronisation of Civilisations of the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C.) project with the notable exception of Kenneth Kitchen and Manfred Bietak at present.

Shabaka

According to the traditional chronology, Shabaka "brought the entire Nile Valley as far as the Delta under the empire of Kush and is 'reputed' to have had Bocchoris, dynast of Sais, burnt to death."[15][7]: 166–167 There is no direct evidence that Shabaqo did slay Bakenranef, and although earlier scholarship generally accepted the tradition, it has recently been treated more skeptically.[31] Initially, Shabaka maintained good relations with Assyria, as shown by his extradition of the rebel, Iamani of Ashdod, to Assyria in 712 BC.[7]: 167 Shabaka supported an uprising against the Assyrians in the Philistine city of Ashdod, however he and his allies were defeated by Sargon II.[citation needed]

Shabaka "transferred the capital to Memphis"[7]: 166 and restored the great Egyptian monuments and temples, "unlike his Libyan predecessors".[7]: 167–169 Shabaka ushered in the age of Egyptian archaism, or a return to a historical past, which was embodied by a concentrated effort at religious renewal and restoration of Egypt's holy places.[7]: 169 Shabaka also returned Egypt to a theocratic monarchy by becoming the first priest of Amon. In addition, Shabaka is known for creating a well-preserved example of Memphite theology by inscribing an old religious papyrus into the Shabaka Stone.

Taharqa

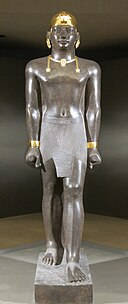

In 690 BC,[7] Taharqa was crowned in Memphis[26] and ruled Upper and Lower Egypt as Pharaoh from Tanis in the Delta.[35][15] Taharqa's reign was a prosperous time in the empire with a particularly large Nile river flood and abundant crops and wine.[36][7] Taharqa's inscriptions indicate that he gave large amounts of gold to the temple of Amun at Kawa.[37] He restored and constructed great works throughout the Nile Valley, including works at Jebel Barkal, Kawa (with Lebanese cedar),[7] Qasr Ibrim, and Karnak.[38][39] "Thebes was enriched on a monumental scale."[7] At Karnak, the Sacred Lake structures, the kiosk in the first court, and the colonnades at the temple entrance are all owed to Taharqa and Mentuemhet. Taharqa and the Kushites marked a renaissance in Pharaonic art.[40] Taharqa built the largest pyramid (52 square meters at base) in the Nubian region at Nuri (near El-Kurru) with the most elaborate Kushite rock-cut tomb.[41] Taharqa was buried with "over 1070 shabtis of varying sizes and made of granite, green ankerite, and alabaster."[42]

Taharqa's army undertook successful military campaigns, as attested by the "list of conquered Asiatic principalities" from the Mut temple at Karnak and "conquered peoples and countries (Libyans, Shasu nomads, Phoenicians?, Khor in Palestine)" from Sanam temple inscriptions.[7] Imperial ambitions of the Mesopotamian based Assyrian Empire made war with the 25th dynasty inevitable. In 701 BC, Taharqa and his army aided Judah and King Hezekiah in withstanding a siege by King Sennacherib of the Assyrians (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9).[43] There are various theories (Taharqa's army,[44] disease, divine intervention, Hezekiah's surrender) as to why the Assyrians failed to take the city and withdrew to Assyria.[45] Torok mentions that Egypt's army "was beaten at Eltekeh" under Taharqa's command, but "the battle could be interpreted as a victory for the double kingdom", since Assyria did not take Jerusalem and "retreated to Assyria."[7]: 170 Many historians claim that Sennacherib was the overlord of Khor following the siege in 701 BC. Sennacherib's annals record Judah was forced into tribute after the siege.[24] However, this is contradicted by Khor's frequent utilization of an Egyptian system of weights for trade,[46] the 20 year cessation in Assyria's pattern (before 701 and after Sennacherib's death) of repeatedly invading Khor,[47] Khor paying tribute to Amun of Karnak in the first half of Taharqa's reign,[7] and Taharqa flouting Assyria's ban on Lebanese cedar exports to Egypt, while Taharqa was building his temple to Amun at Kawa.[48] Sennacherib was murdered by his own sons in revenge for the destruction of the rebellious Mesopotamian city of Babylon, a city sacred to all Mesopotamians, the Assyrians included.[citation needed]

In 679 BC, Sennacherib's successor, King Esarhaddon, campaigned into Khor and took a town loyal to Egypt. After destroying Sidon and forcing Tyre into tribute in 677-676 BC, Esarhaddon invaded Egypt in 674 BC. Taharqa and his army defeated the Assyrians outright in 674 BC, according to Babylonian records.[49] Taharqa's Egypt still held sway in Khor during this period as evidenced by Esarhaddon's 671 BC annal mentioning that Tyre's King Ba'lu had "put his trust upon his friend Taharqa", Ashkelon's alliance with Egypt, and Esarhaddon's inscription asking "if the Egyptian forces will defeat Esarhaddon at Ashkelon."[50] However, Taharqa was defeated in Egypt in 671 BC when Esarhaddon conquered Northern Egypt, captured Memphis, imposed tribute, and then withdrew.[35] In 669 BC, Taharqa reoccupied Memphis, as well as the Delta, and recommenced intrigues with the king of Tyre.[35] Esarhaddon again led his army to Egypt and on his death, the command passed to Ashurbanipal. Ashurbanipal and the Assyrians advanced as far south as Thebes, but direct Assyrian control was not established."[35] Taharqa retreated to Nubia, where he died in 664 BC.

Taharqa remains an important historical figure in Sudan and elsewhere, as is evidenced by Will Smith's recent project to depict Taharqa in a major motion picture.[51] As of 2017, the status of this project is unknown.

A study of the sphinx that was created to represent Taharqa indicates that he was a Kushite pharaoh from Nubia.[52]

Tantamani

Taharqa's successor, Tantamani sailed north from Napata, through Elephantine, and with a large army to Thebes, where he was "ritually installed as the king of Egypt."[7]: 185 From Thebes, Tantamani began his reconquest[7]: 185 and regained control of Egypt, as far north as Memphis.[35] Tantamani's dream stele states that he restored order from the chaos, where royal temples and cults were not being maintained.[7]: 185 After defeating Sais and killing Assyria's vassal, Necho I, in Memphis, "some local dynasts formally surrendered, while others withdrew to their fortresses."[7]: 185 Tantamani proceeded north of Memphis, invading Lower Egypt and, besieged cities in the Delta, a number of which surrendered to him.[citation needed]

Necho's son Psamtik I fled Egypt to Assyria and returned in 664 BC with Ashurbanipal and a large army comprising Carian mercenaries.[citation needed] Upon the Assyrians arrival in Egypt, Tantamani fled to Thebes, where he was pursued by the Assyrians.[7]: 186–187 Then, Tantamani escaped to Nubia and the Assyrian army sacked Thebes "and devastated the area" in 663 BC[35] Psamtik I was placed on the throne of Lower Egypt as a vassal of Ashurbanipal.[citation needed] Psamtik quickly unified Lower Egypt and expelled the Assyrian army, becoming the first ruler of the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty.[7]: 186 In 656 BC, Psamtik sent a large fleet southwards to Thebes, peacefully taking control of the still rebellious Upper Egypt thereby unifying all of Egypt.

Tantamani and the Nubians never again posed a threat to either Assyria or Egypt. Upon his death, Tantamani was buried in the royal cemetery of El-Kurru, upstream from the Kushite capital of Napata. He was succeeded by a son of Taharqa, king Atlanersa.[24] In total, the Twenty-fifth Dynasty ruled Egypt for less than one hundred years.[5][53] The successors of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty settled back in their Nubian homeland, where they continued their kingdom at Napata (656–590 BC), and continued to make empty claims to Egyptian kingship during the next 60 years, while the effective control of Egypt was in the hands of Psamtik I and his successors.[54] The Kushite next ruled further south at Meroë (590 BC – 4th century AD).[24]

Armies of the 25th dynasty

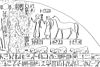

The Nubian/Egyptian soldiers of the 25th dynasty are represented in a few Assyrian reliefs related to the Assyrian conquest of Egypt, such as the Siege of an Egyptian fort in 667 BC. Nubian soldiers defending their city are represented, as well as prisoners under Assyrian escort, many wearing the typical one-feathered headgear of Taharqa's soldiers.[55][56]

-

Armoured Kushite soldiers of Taharqa defending their city from the Assyrian assault

Armoured Kushite soldiers of Taharqa defending their city from the Assyrian assault -

![Nubian prisoners escorted by Assyrian guards out of the Egyptian city.[55]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d0/Exhibition_I_am_Ashurbanipal_king_of_the_world%2C_king_of_Assyria%2C_British_Museum_%2845973251301%29.jpg/200px-Exhibition_I_am_Ashurbanipal_king_of_the_world%2C_king_of_Assyria%2C_British_Museum_%2845973251301%29.jpg) Nubian prisoners escorted by Assyrian guards out of the Egyptian city.[55]

Nubian prisoners escorted by Assyrian guards out of the Egyptian city.[55] -

![Nubian prisoners.They wear the typical one-feathered headgear of Taharqa's soldiers.[55]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/Egyptian_prisoners%2C_Memphis_relief.jpg/198px-Egyptian_prisoners%2C_Memphis_relief.jpg) Nubian prisoners.They wear the typical one-feathered headgear of Taharqa's soldiers.[55]

Nubian prisoners.They wear the typical one-feathered headgear of Taharqa's soldiers.[55]

Revenge of Psamtik II

Psamtik II, the third ruler of the following dynasty, the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty, deliberately destroyed monuments belonging to the 25th Dynasty of Kushite kings in Egypt, erasing their names and their emblems of royalty from statues and reliefs in Egypt. He then sent an army to Nubia in 592 BCE to erase all traces of their rule, during the reign of the Kushite King Aspelta. This expedition and its destructions are recorded on several victory stelae, especially the Victory Stela of Kalabsha. The Egyptian army "may have gone on to sack Napata, although there is no good evidence to indicate that they actually did so."[35]: 65 This led to the transfer of the Kushite capital farther south at Meroë.[57][58]

Art and architecture

Although the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty controlled Ancient Egypt for only 91 years (747–656 BC), it holds an important place in Egyptian history due to the restoration of traditional Egyptian values, culture, art, and architecture.

The Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt revived the lost Egyptian tradition of building pyramids for their deceased rulers. Nubian kings built their own pyramids 1000 years after Egyptian burial methods had changed.[59] Nubian pyramids were built for the first time at El Kurru in 751 BC, for the Piye, the first ruler of the 25th Dynasty, and more were built at Nuri.[60] The Nubian-style pyramids emulated a form of Egyptian private elite family pyramid that was common during the New Kingdom (1550-1069 BC).[61] There are twice as many Nubian pyramids still standing today as there are Egyptian.[59]

Pharaohs of the 25th Dynasty

The pharaohs of the 25th Dynasty ruled for approximately 91 years in Egypt, from 747 BC to 656 BC.

| Pharaoh | Image | Prenomen (Throne name) | Horus-name | Reign | Pyramid | Consort(s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piye |  | Usimare | Kanakhtkhaemnepet | c. 747–714 BC | Kurru 17 | Kashta is sometimes considered the first pharaoh of the dynasty, as opposed to Piye. | |

| Shebitku |  | Djedkare | Djedkhau | 714–705 BC | Kurru 18 | Arty (Kurru 6) | |

| Shabaka |  | Neferkare | Sebaqtawy | 705–690 BC | Kurru 15 |

| |

| Taharqa |  | Khunefertumre | Qakhau | 690–664 BC | Nuri 1 |

| |

| Tantamani |  | Bakare | Wahmerut | 664–656 BC | Kurru 16 |

| Lost control of Upper Egypt in 656 BC when Psamtik I captured Thebes in that year. |

The period starting with Kashta and ending with Malonaqen is sometimes called the Napatan Period. The later Kings from the twenty-fifth dynasty ruled over Napata, Meroe, and Egypt. The seat of government and the royal palace were in Napata during this period, while Meroe was a provincial city. The kings and queens were buried in El-Kurru and Nuri.[63]

Alara, the first known Nubian king and predecessor of Kashta was not a 25th dynasty king since he did not control any region of Egypt during his reign. While Piye is viewed as the founder of the 25th dynasty, some publications may include Kashta who already controlled some parts of Upper Egypt. A stela of his was found at Elephantine and Kashta likely exercised some influence at Thebes (although he did not control it) since he held enough sway to have his daughter Amenirdis I adopted as the next Divine Adoratrice of Amun there.

Timeline of the 25th Dynasty

See also

| Periods and dynasties of ancient Egypt | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All years are BC | ||||||||||||||||||

| Early

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| See also: List of pharaohs by period and dynasty Periodization of ancient Egypt | ||||||||||||||||||

|

- Aethiopia is an ancient Greek geographical term which referred to the regions of Sudan and areas south of the Sahara desert.

- History of Ancient Egypt

- List of monarchs of Kush

- Twelfth dynasty of Egypt

- Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt family tree

References

- ^ Elshazly, Hesham. "Kerma and the royal cache".

- ^ a b "Dive beneath the pyramids of Sudan's black pharaohs". National Geographic. 2 July 2019. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019.

- ^ Morkot, Robert (2000). The black pharaohs : Egypt's Nubian rulers. London: Rubicon Press. ISBN 0-948695-23-4. OCLC 43901145.

- ^ Oliver, Roland (5 March 2018). The African Experience: From Olduvai Gorge to the 21st Century. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-429-97650-6.

The Napatans, somewhere around 900 BC conquered both Lower and Upper Nubia, including the all-important gold mines, and by 750 were strong enough to conquer Egypt itself, where their kings ruled for nearly a century as the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty

- ^ a b "Nubia | Definition, History, Map, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Bard, Kathryn A. (7 January 2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons. p. 393. ISBN 978-1-118-89611-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Török, László (1998). The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 132–133, 153–184. ISBN 90-04-10448-8.

- ^ "King Piye and the Kushite control of Egypt". Smarthistory. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Heinrich, Brugsch (1902). A history of Egypt under the Pharaohs. John Murray London. p. 387.

- ^ Breasted, J.H. (1924). A History of Egypt from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest. Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 538–539.

- ^ Drioton, E. (1962). Drioton, E; Vandier, J – Les Peuples de l'Orient Méditerranéen II L' Egypte. Paris: Presses universitaires de France. pp. 524, 537–538.

- ^ Assmann, Jan (2002). The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs. Metropolitan Books. pp. 317–321.

- ^ Wenig, Steffen (1999). The origin of the Napatan state: El Kurru and the evidence for the royal ancestors. In Studien zum antiken Sudan: Akten der 7. Internationalen Tagung für meroitische Forschungen vom 14. bis 19. September 1992 in Gosen/bei Berlin. Harrassowitz; Bilingual edition. pp. 3–117.

- ^ Bonnet, Charles (2006). The Nubian Pharaohs. New York: The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 142–154. ISBN 978-977-416-010-3.

- ^ a b c d Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ^ a b c d Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- ^ a b Silverman, David (1997). Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-19-521270-3.

- ^ Logan, Jim (21 September 2020). "The African Egypt". The Current / UC Santa Barbara.

Smith, who has been excavating the ancient site of Tombos in modern Sudan (Nubia) since 2000, has focused his research on questions of identity, especially ethnicity, and intercultural interaction between ancient Egypt and Nubia. In the 8th century BCE, he noted, Kushite rulers were crowned as Kings of Egypt, ruling a combined Nubian and Egyptian kingdom as pharaohs of Egypt's 25th Dynasty. Those Kushite kings are commonly referred to as the 'Black Pharaohs' in both scholarly and popular publications. That terminology, Smith said, is often presented as a celebration of black African civilization. But it also reflects a longstanding bias that holds the Egyptian pharaohs and their people weren't African — that is, not Black. It's a trope that feeds into a long history of racism that traces back to the some of the founding figures of Egyptology and their role in the creation of "scientific" racism in the U.S. [...] 'It has always struck me as odd that Egyptologists have been reluctant to admit that the ancient (and modern) Egyptians were rather dark-skinned Africans, especially the farther south one goes," Smith continued.

- ^ "One of the other problems with the "Black Pharaohs" monikor is that it implies that none of the other Predynastic, Protodynastic, or dynastic Egyptian rulers could be called "black" - in the sense of the Kushites - which, while not particularly interesting, is not true. Even Sir Flinders Petrie, father of the Asiatic "Dynastic Race" theory of dynastic Egypt's foundation, stated that various other dynasties were of "Sudany" origin or had connections there, based on phenotype; which implies [incorrectly] that particular traits could not have been Egyptian i.e. been a part of its ancestral biological variation".Keita, S. O. Y. (September 2022). "Ideas about "Race" in Nile Valley Histories: A Consideration of "Racial" Paradigms in Recent Presentations on Nile Valley Africa, from "Black Pharaohs" to Mummy Genomest". Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections.

- ^ Crawford, Keith W. (2021). "Critique of the "Black Pharaohs" Theme: Racist Perspectives of Egyptian and Kushite/Nubian Interactions in Popular Media". African Archaeological Review. 38 (4): 695–712. doi:10.1007/s10437-021-09453-7. ISSN 0263-0338. S2CID 238718279.

- ^ Herodotus (2003). The Histories. Penguin Books. pp. 106–107, 133–134. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- ^ Leahy, Anthony (1992). "Royal Iconography and Dynastic Change, 750-525 BC: The Blue and Cap Crowns". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 78: 227, and Plate XXVI. doi:10.2307/3822074. ISSN 0307-5133. JSTOR 3822074.

- ^ Lichtheim, Miriam (1980). Ancient Egyptian Literature: A Book of Readings. University of California Press. pp. 66–75. ISBN 978-0-520-04020-5.

- ^ a b c d Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq (Third ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-012523-X.

- ^ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ^ a b c Haynes, Joyce (1992). Harvey, Fredrica (ed.). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Museum of Fine Arts. pp. 25–30. ISBN 0-87846-362-3.

- ^ a b c Payraudeau, F. (2014). "Retour sur la succession Shabaqo-Shabataqo" (PDF). Nehet. 1: 115–127.

- ^ a b Broekman, Gerard P. F. (2017). "Genealogical considerations regarding the kings of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty in Egypt". Göttinger Miszellen. 251: 13–20. ISSN 0344-385X.

- ^ Kahn, Dan'el (2001). "The Inscription of Sargon II at Tang-i Var and the Chronology of Dynasty 25". Orientalia. 70 (1): 1–18. JSTOR 43076732.

- ^ Sidebotham, Steven E. (2002). "Newly Discovered Sites in the Eastern Desert". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 82: 181–192 [p. 182 n. 24]. doi:10.1177/030751339608200118. JSTOR 3822121. S2CID 192102954.

- ^ Wenig, Steffen (1999). Studien Zum Antiken Sudan: Akten Der 7. Internationalen Tagung Für Meroitische Forschungen Vom 14. Bis 19. September 1992 in Gosen/bei Berlin. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 203. ISBN 978-3-447-04139-3.

- ^ Smith, William Stevenson; Simpson, William Kelly (1 January 1998). The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt. Yale University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-300-07747-6.

- ^ Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life of the Nubians. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-313-32501-4.

- ^ "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ a b c d e f g Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 0-7141-0986-X.

- ^ Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. p. 158. ISBN 0-7141-0986-X.

- ^ Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-7141-0986-X.

- ^ Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. pp. 16–34, 62–64, 175, 183. ISBN 0-7141-0986-X.

- ^ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 219–221. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ^ Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-7141-0986-X.

- ^ Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. pp. 103, 107–108. ISBN 0-7141-0986-X.

- ^ Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-7141-0986-X.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 141–144. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 127, 129–130, 139–152. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 119. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 155–156. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 152–153. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 155. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 158–161. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 159–161. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (7 September 2008). "Will Smith puts on 'Pharaoh' hat". Variety. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ Nöthling, F. J. (1989). Pre-Colonial Africa: Her Civilisations and Foreign Contacts. Southern Book Publishers. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-86812-242-4. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

He moved his capital to Thebes and became king of Kush and Misr (Egypt) forming the 25th dynasty. Kushite power stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the present Ethiopian boundary. Some Egyptians welcomed the Kushite presence and saw them as civilised people and not as barbarians. Their culture was a mixture of indigenous Egyptian and Sudanese elements and physically their appearance included Egyptian, Berber-Libyan and other Mediterranean elements as well as the Negroid blood coming from the region of the fifth and sixth cataracts

- ^ "Kushite Kingdom | The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago". oi.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ "The next six decades, they and their successors would continue to make fictive claims to Egyptian kingship" Kendall, Timothy. Jebel Barkal Guide (PDF). p. 6.

- ^ a b c "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life of the Nubians. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-313-32501-4.

- ^ Leahy, Anthony (1992). "Royal Iconography and Dynastic Change, 750-525 BC: The Blue and Cap Crowns". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 78: 238. doi:10.2307/3822074. ISSN 0307-5133. JSTOR 3822074.

- ^ Elshazly, Hesham. Kerma and the royal cache. pp. 26–77.

- ^ a b Takacs, Sarolta Anna; Cline, Eric H. (17 July 2015). The Ancient World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45839-5.

- ^ Mitchell, Joseph; Mitchell, Helen Buss (27 March 2009). Taking Sides: Clashing Views in World History, Volume 1: The Ancient World to the Pre-Modern Era, Expanded. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-812758-8.

- ^ Kolb, Michael J. (6 November 2019). Making Sense of Monuments: Narratives of Time, Movement, and Scale. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-76492-9.

- ^ Smith, William Stevenson; Simpson, William Kelly (1 January 1998). The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt. Yale University Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-300-07747-6.

- ^ Dunham, Dows (1946). "Notes on the History of Kush 850 BC – A.D. 350". American Journal of Archaeology. 50 (3): 378–388. doi:10.2307/499459. JSTOR 499459. S2CID 193086188.

Further reading

- Reisner, G. A. (1919). "Discovery of the Tombs of the Egyptian XXVth Dynasty". Sudan Notes and Records. 2 (4): 237–254. JSTOR 41715805.

- Morkot, R. G. (2000). The Black Pharaohs, Egypt's Nubian Rulers. London: Rubicon Press.

External links

Media related to 25th dynasty of Egypt at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 25th dynasty of Egypt at Wikimedia Commons- (in French) Voyage au pays des pharaons noirs Travel in Sudan : pictures and notes on the Nubian history

![Nubian prisoners escorted by Assyrian guards out of the Egyptian city.[55]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d0/Exhibition_I_am_Ashurbanipal_king_of_the_world%2C_king_of_Assyria%2C_British_Museum_%2845973251301%29.jpg/200px-Exhibition_I_am_Ashurbanipal_king_of_the_world%2C_king_of_Assyria%2C_British_Museum_%2845973251301%29.jpg)

![Nubian prisoners.They wear the typical one-feathered headgear of Taharqa's soldiers.[55]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/Egyptian_prisoners%2C_Memphis_relief.jpg/198px-Egyptian_prisoners%2C_Memphis_relief.jpg)

![The famous column of Taharqa with open papyrus capital, in Karnak, Thebes (one remaining of ten).[62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f6/Karnak_R03.jpg/72px-Karnak_R03.jpg)